In a world racing towards climate catastrophe and global biodiversity meltdown, there is one scientific breakthrough that defies the script—not just to prevent extinction, but to reverse it.

In 2024, researchers from Colossal Biosciences announced the birth of three dire wolf pups—a species extinct for over 12,000 years. The Dallas company claims to have resurrected a predator that once dominated North America using ancient DNA reconstruction and non-invasive gene editing and cloning.

The achievement sparked both awe and controversy while challenging our understanding of extinction, ethics, and our capability to redefine nature. While its advocates describe it as a triumph of biotechnology, critics question whether these hybrids can ever replace the ecological or evolutionary legacy of their Ice Age ancestors.

The Resurrection Begins: Dire Wolves Return from the Ice Age

The dire wolf, a premier predator of the Pleistocene epoch, is back—sort of. Thanks to breakthroughs in de-extinction and reproductive cloning, a dire wolf-like hybrid pup was recently born, resurrecting one of the most iconic animals of prehistory.

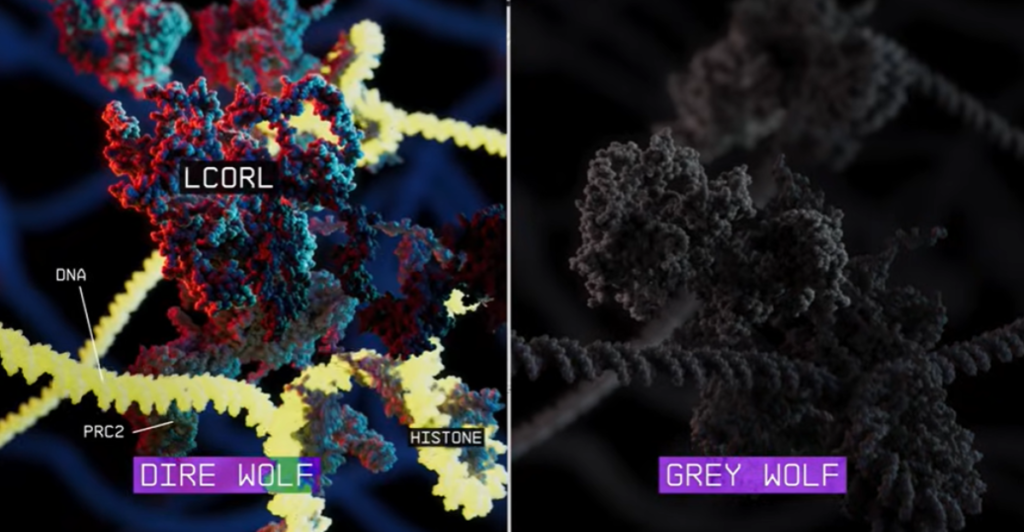

Spearheaded by Colossal Biosciences, the team extracted DNA from a 13,000-year-old dire wolf tooth and a 72,000-year-old skull fragment and sequenced the species’ genome for the first time. They edited gray wolf cells—its closest living relative, which shares a 97% genetic similarity—to make 20 targeted genetic edits and created embryos implanted in surrogate wolves.

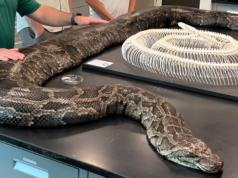

The pups, Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi, have wider skulls, thicker coats, and a 25% greater body weight than modern wolves. Genetically speaking, they are not 100% dire wolves. However, they represent a new form of “functional de-extinction.”

The Dire Wolf’s Ancient World

Dire wolves (Aenocyon dirus) reigned for 2 million years, feeding on megafauna such as bison and mastodons. They became extinct due to climate shifts and human competition, which is mirrored in today’s biodiversity crisis.

Based on fossil evidence, particularly the two preserved specimens used to sequence the dire wolf genome suggests that these wolves were similar to gray wolves but were larger, more muscular, and had long, thick light-colored fur.

However, genomic studies have shown that dire wolves split from the canid genus roughly 5.7 million years ago, showing no signs of genetic exchange with North America’s gray wolf ancestral populations. This contributes to arguments that Colossal has not resurrected a true dire wolf.

Ancient Code, Modern Tools: CRISPR and Non-Invasive Cloning

Colossal Biosciences, a company known to be working on restoring the woolly mammoth and dodo bird, used sophisticated CRISPR gene editing and somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) to create the three dire wolf pups. The project cost roughly $100 million and has resulted in a hybrid species similar in appearance to its ancient ancestors.

The dire wolf pups were born through surrogate Mexican gray wolf—an endangered species itself—through techniques that avoided embryo destruction or live tissue extraction, making the process ethically cleaner and safer.

The team used newer techniques than past cloning attempts by merging ancient and modern DNA, which was more precise and minimally invasive. CRISPR-Cas9 enabled specific changes to the gray wolf genome and the insertion of 20 extinct genetic traits linked to size, coat thickness, and jaw power.

Dire or Different? The Hybrid Controversy

Contrary to reports, the resulting animal is not a “pure” dire wolf. Scientists refer to it as a hybrid—technically a modern wolf with dire wolf-like traits. This presents a basic argument: If it looks, acts, and survives like a dire wolf, is it one?

Critics argue that Colossal did not resurrect an extinct creature but created a proxy. Advocates believe that functional restoration is more important than genetic purity, especially if these hybrids can restore ecological balance.

Further, scientists ponder the validity of “resurrecting” the species given that North America has lost 40% of its large mammal biomass since the Pleistocene era, meaning that the dire wolf restoration may prove obsolete in our current fragmented, urbanized ecosystem.

Lessons from Lazarus Species

The woolly mammoth and passenger pigeon dominate de-extinction debates, but the dire wolf’s return offers a realistic lesson. Unlike mammoths, wolves have living relatives, so genetic gaps are easier to fill.

Even this “easy” one took 12 years of research—a reality check for exaggerated timelines. Colossal’s 2013 vow to restore mammoths by 2027 is still not fulfilled, highlighting the gap between promise and performance.

However, many argue that species resurrection cannot be fully achieved without cloning ancient species’ DNA. Something that may prove impossible because DNA samples taken from fossilized specimens are often not preserved well enough to allow scientists to map out their full genomes. Dr. Beth Shapiro, a paleogeneticist, notes that even 95% genetic accuracy might fail to restore species.

De-Extinction: A New Scientific Discipline and its Economics

This breakthrough gave rise to paleogenomics, a discipline where ancient DNA converges with synthetic biology. By reconstructing extinct animals from degraded genetic remnants, scientists are turning paleontology into an active engineering science, merging archaeology, genomics, AI, and conservation fields.

Furthermore, there’s big money in the species revival industry. Colossal Biosciences has raised over $225 million and aims to de-extinct several species. To do so, companies are leveraging extinct species as “keystone disruptors” to heal damaged ecosystems, monetizing biotech patents, and using conservation technology.

From carbon capture credits to genetic licensing, de-extinction is a whole new industry. But it raises the question: what’s the outcome when profit motives encounter nature? If history is any indication, commercializing animal life often leads to exploitation. The tug-of-war between venture capitalism and ecological salvation may define the next decade of de-extinction.

Ecosystem Rewind or Biohack Fail? The Ecological Gamble

Ecologically, restoring top predators like dire wolves may rebalance destabilized ecosystems. For example, Yellowstone’s wolves famously revived whole ecosystems, proving top-down restoration works. Yet inserting a long-extinct predator into modern biomes is a wild card.

Ecosystems, prey populations, and the climate are not what they were 12,000 years ago. A resurrected species could become invasive, revive ancient diseases, or disrupt food webs. Further, as apex predators, the dire wolves might compete with modern wolves or cattle.

For example, in 2023, CRISPR-gen edited mosquito introductions in Florida triggered unanticipated butterfly population declines, showing the domino effect of domesticated species. Therefore, without long-term research, every new birth is a biological experiment, one whose ripple effects we cannot fully anticipate as yet.

From Fossils to Film: Pop Culture’s Role in Driving Science

Let’s be real—de-extinction wouldn’t have billions in backing without popular movies, such as Jurassic Park, and series, such as Game of Thrones. Fiction, it seems, inspires public interest and investment.

Colossal Biosciences CEO Ben Lamm credits the film as inspiration. But instead of rampaging T. rexes, we have wolf pups in conservation enclosures. The female pup is even named after Game of Thrones’ mother of dragons, “Khaleesi,” further showing that returning species for cultural significance may be prioritized over ecological significance.

Moreover, pop culture’s grip on science has risks: headline-making promises and simplified narratives can lead to public backlash when things go wrong. Still, the media allure of “resurrected monsters” can incite political and philanthropic support in a way that scientific papers cannot.

The Long Game: What De-Extinction Means for Humanity

This is not just about wolves and woolly mammoths. De-extinction forces us to question our fundamental relationship with life, death, and evolution. Are we stewards or creators? The dire wolf cubs symbolize a time when extinction will no longer be permanent—when biotech enables us to code biodiversity.

However, there are risks to that future, but also radical hope. Instead of mourning species, we might rescue them. Instead of fearing nature’s degradation, we might reverse it. Conversely, if we restore what we’ve lost, we must protect what we still have.

De-extinction is not resurrection—it’s reinvention. As biotech meets conservation, we now have the power to breathe life back into ancient worlds. With that power comes difficult questions regarding ethics, ecology, and our evolutionary responsibilities.

Explore more of our trending stories and hit Follow to keep them coming to your feed!

Don’t miss out on more stories like this! Hit the Follow button at the top of this article to stay updated with the latest news. Share your thoughts in the comments—we’d love to hear from you!