Most fish live five, maybe ten years if they’re lucky. But the one recently discovered in the Pacific Ocean? It’s clocked in over two hundred.

It’s been quietly drifting through deep, icy waters since before steamships ruled the seas. Hidden in near-freezing darkness, this fish has survived world wars, climate shifts, and generations of human activity without anyone even noticing.

Now researchers are scrambling to learn what it’s hiding in its DNA, and how it’s still alive after all this time.

You’re not going to believe where it was hiding. Let’s get into it.

Scientists Were Chasing a Rumor. Then They Found Proof.

Marine biologists have long suspected that there are creatures with lifespans that could make elephants look short-lived. The hunt became serious when researchers began testing deep-sea fish using radiocarbon markers left behind by nuclear bomb tests in the 1950s.

Those tests, embedded in the environment, helped age-old tissue samples like tree rings. The findings shocked everyone. One fish had been alive since the early 1800s. The mystery of what kind of fish this could be was about to be solved.

The oldest living fish ever recorded in Pacific waters

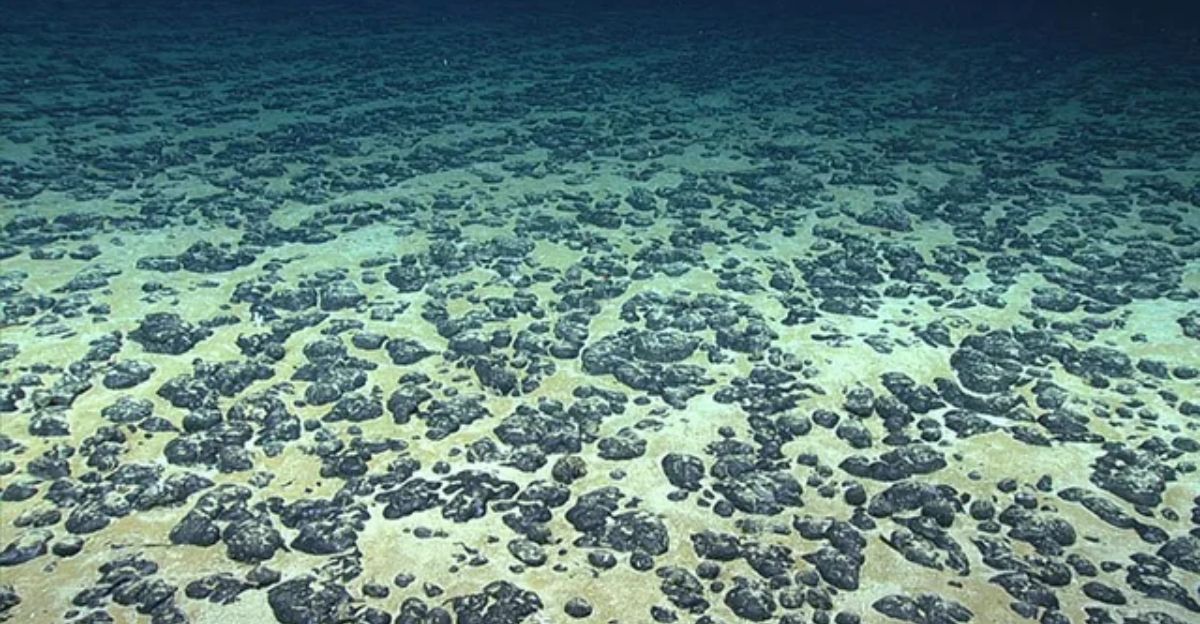

Say hello to the rougheye rockfish, a cold-water dweller with a lifespan that can stretch over two centuries. This deep-sea species prefers depths between 150 and 450 meters and blends in so well with rocky seafloors that it managed to avoid serious study for decades.

Its name comes from the jagged spines that ring its eyes, but its legacy comes from its age. One verified specimen lived over 200 years, making it the oldest known fish in Pacific waters.

So how did it live so long? The answer lies in the cold.

How Freezing Water Slows Down Time

The rougheye rockfish owes its remarkable lifespan to the harsh conditions of the deep sea. At near-freezing temperatures with low oxygen levels, its metabolism slows to a crawl. This process, called “metabolic refrigeration,” minimizes cellular damage and delays aging.

Add to that the stable pressure and minimal environmental changes of the deep ocean, and you’ve got a natural anti-aging chamber. Unlike shallow-water species, these fish avoid the wear and tear of fluctuating conditions. In fact, depth now serves as a major clue in predicting fish longevity.

But surviving this long didn’t just take the right environment; it took smart hiding, too.

Why We Missed It for 200 Years

It wasn’t hiding at the bottom of a trench. It was just really good at going unnoticed. The rougheye rockfish lives in a depth range that most fishing gear avoids and most research teams rarely explore.

Even when caught, traditional aging methods failed, and counting growth rings in bones stopped working past 50 years. Only with modern radiocarbon dating could researchers finally uncover its age. The kicker? The telltale timestamp came from atomic bomb residue lodged in the fish’s tissue. This method didn’t exist until recently, which is why this centuries-old fish stayed under the radar for so long.

Now scientists are digging even deeper; into its DNA.

Cracking the Genetic Code of Longevity

When scientists sequenced the genomes of 88 rockfish species, they found a pattern. The longest-lived species had built-in advantages: better DNA repair, stronger antioxidant systems, and rare gene pathways that regulate insulin and reduce inflammation.

One group of genes appeared to help prevent cellular aging, the kind that leads to cancer and disease. These ancient fish stay healthier while doing it. Some of their longevity traits even line up with genetic markers in human aging research. It’s no wonder scientists call them living laboratories.

And this lab plays a critical role in keeping ocean ecosystems stable.

The Ocean’s Slowest but Strongest Anchors

Rougheye rockfish aren’t just survivors, they’re essential. Their role in the food web helps stabilize deep-sea ecosystems. They eat small fish and crustaceans and serve as prey for larger predators, keeping populations in balance. Because they take decades to mature, a damaged population can take over a century to recover.

These fish also store chemical records in their tissue, making them valuable trackers of long-term ocean changes. Marine reserves in places like California have already shown that protecting them increases overall biodiversity.

But just as they’re being recognized for their value, they’re facing a serious threat: human fishing habits.

We’re Accidentally Killing Off Two-Century-Old Fish

Here’s the problem: these fish live forever, but they die just like any other catch. Industrial trawling often scoops them up by mistake. A single dead rougheye rockfish could erase 200 years of evolution, adaptation, and ecological history.

Even worse, they don’t reproduce quickly. If a population drops, recovery can take generations. Many species were overfished in the early 2000s and are still struggling to bounce back. Current fishing regulations, built for fast-growing species, don’t account for creatures that live for centuries.

The longer we wait, the harder it becomes to save them. And the clock is ticking.

The Race to Protect What’s Left

The discovery of these ancient survivors has pushed conservation efforts into overdrive. In 2024, Pacific Island nations created marine protected zones covering over a billion hectares. It’s a huge step, but risks still loom.

Deep-sea mining and expanding fisheries are creeping into untouched habitats, and rising ocean temperatures could force cold-adapted species like the rougheye into dangerous territory. This year alone, over 100 previously unknown species were discovered in deep Pacific waters. The ocean is still full of surprises, but many of them may disappear before we fully understand what we’ve found.

Which brings us to the final question: what happens next?

Can We Learn to Think in Centuries?

Rougheye rockfish remind us that life can move slowly and still be powerful. They show that survival isn’t about speed or dominance, but patience, balance, and resilience.

As the climate crisis deepens and ecosystems falter, we’re being handed a biological case study in endurance. These fish survived ice ages, volcanic eruptions, and centuries of natural change.

But can they survive us? Their story is more than fascinating; it’s a warning and a challenge. Can we shift from short-term exploitation to long-term stewardship? Or will we let the wisdom of centuries vanish in silence, one net at a time? The future is watching. So is the deep.