Utah’s Wasatch Fault is a giant that the public is yet to face, and after being quiet for centuries, it might start rumbling soon enough. Recent scientific discoveries have begun to unravel why this fault is not just active, but uniquely primed for a major earthquake, raising urgent questions about the risks lurking beneath the surface. Why is this fault causing so much unease in the scientific community, and why are they claiming that the next big quake is long overdue?

Get to Know the Wasatch Fault

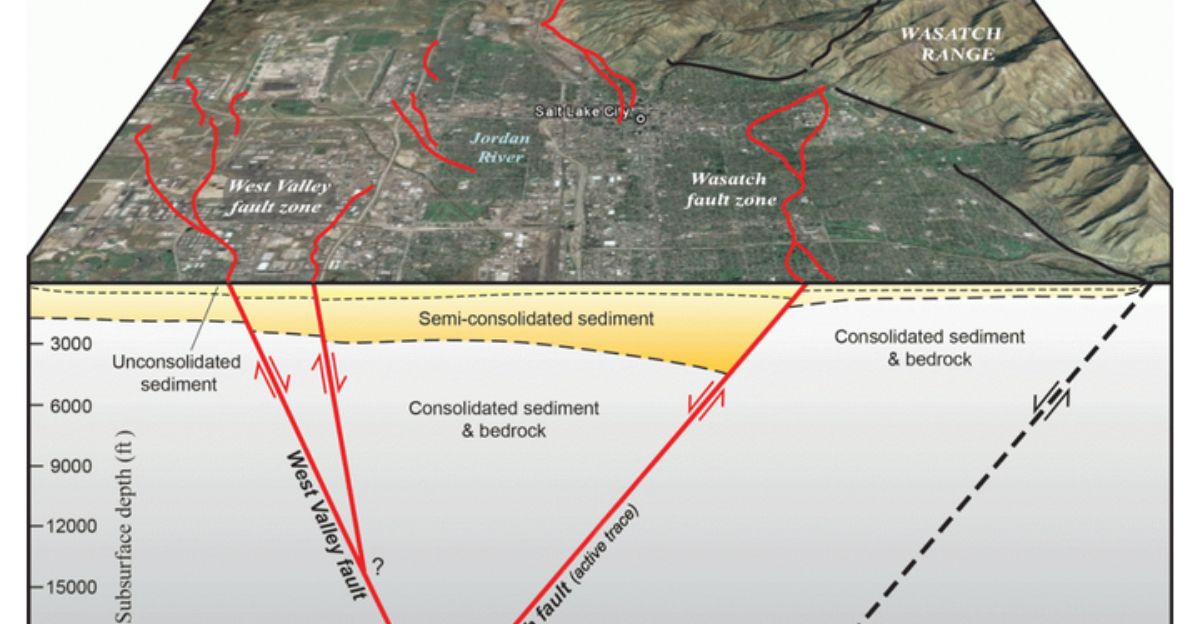

This major fault runs roughly 240 miles along the western base of Utah’s Wasatch Mountains, from southern Idaho to central Utah. It is not just a single crack in the earth, but a complex zone of parallel faults and deformed ground, often marked by steep escarpments that are visible as dramatic breaks at the foot of the mountains.

“The Wasatch Fault forms the eastern edge of the Basin and Range geologic province, which has stretched and broken over millions of years,” says Srisharan Shreedharan, a geophysicist at Utah State University. The Wasatch Fault passes through or near many of Utah’s largest cities, Salt Lake City, Provo, and Ogden, placing about 80% of the state’s population within its reach.

A Fault Divided

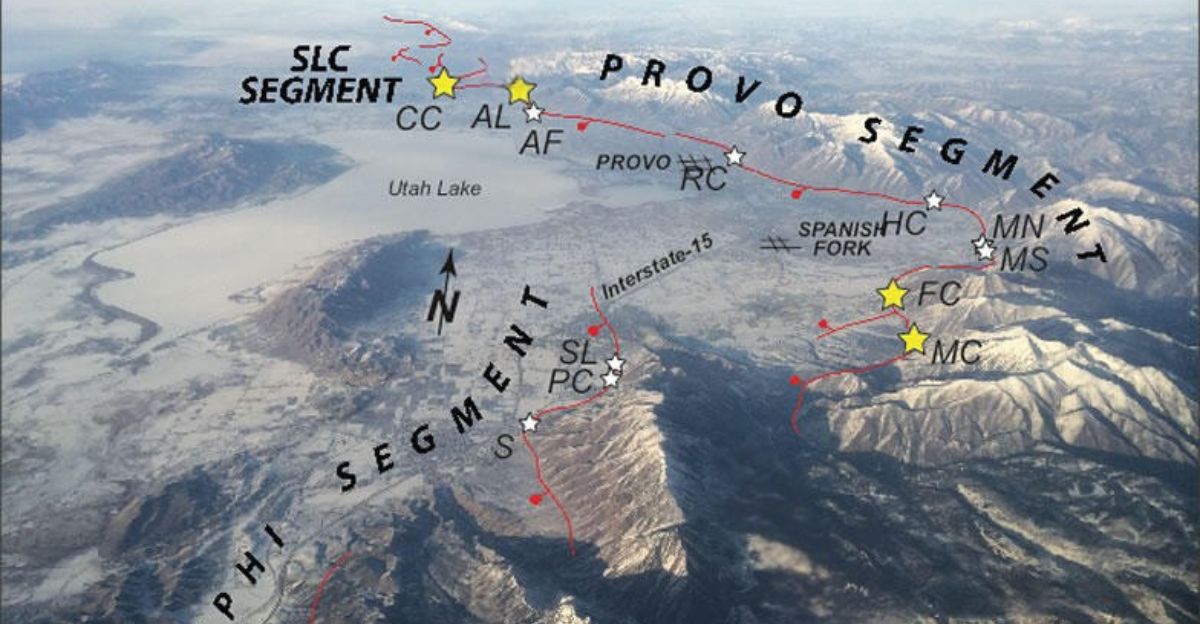

The Wasatch Fault is not a single unbroken crack but a system divided into ten segments, five of which are currently considered active. Each segment averages about 25 miles in length and can independently produce significant earthquakes, with the potential for magnitudes up to 7.5. These segments act as their earthquake zones, but determining where their boundaries end isn’t always possible. Geological and geophysical studies reveal that these segments are separated by subtle changes in rock types, gravity signatures, and fault geometry, influencing how and where ruptures occur.

The activity along these segments is shaped by the fault’s role as a normal fault at the edge of the Basin and Range Province, where the earth’s crust is being pulled apart, causing the hanging wall to drop steeply relative to the footwall. “The dip angle of the sliding surface tends to be steep, often between 45 and 90 degrees,” he says. “The Wasatch Fault plunges, toward the west, at a steep angle at the surface in the Salt Lake City area.”

Why the Wasatch Fault Is So Dangerous

The Wasatch Fault is normal, meaning one side of the Earth’s crust moves downward relative to the other. With over 80% of Utah’s population living within 15 miles of the fault, even a moderate earthquake could devastate densely populated cities like Salt Lake City, Provo, and Ogden. Take into account that these segmented structures can each generate their quakes, which makes this fault all the more terrifying.

“Although the Wasatch Fault dips sharply at Salt Lake City, it curves more gently at depth as it moves west and is probably oriented at a much shallower angle at earthquake depth than expected,” Shreedharan says. “This means that an earthquake rupture could lead to stronger, more intense shaking at the surface, meaning a greater chance of injury and destruction.” Beneath urban centers lie ancient lakebed sediments prone to liquefaction, where saturated soil loses strength during shaking, destabilizing buildings and infrastructure, making this even more risky.

The Science of Overdue Earthquakes

Earthquakes are unpredictable, and even though we have the technology to warn us of an oncoming quake, it’s technically possible to determine when a big one will happen. Researchers can make estimations based on previous quakes and research, but the unease they cause is more daunting than the actual warning. Geological studies showed that major earthquakes (magnitude 7.0 or greater) happen on the central segments of the Wasatch Fault every 900–1,300 years.

Taking that information into account, the Salt Lake City segment last ruptured about 1,200–1,300 years ago, and the Brigham City segment has not ruptured in over 2,200 years, making the region statistically overdue for a large event.

The 2020 Magna Earthquake

On the morning of March 18, 2020, Utah was jolted by a magnitude 5.7 earthquake centered just north of Magna, about 10 miles west of downtown Salt Lake City. The quake struck at 7:09 a.m., shaking homes and businesses across the Wasatch Front and was felt by nearly three million residents. This was believed to be the biggest earthquake to hit Salt Lake City since pioneer settlement.

“But the 2020 Magna earthquake, which occurred at about 9 kilometers depth west of Salt Lake City, caused injuries and resulted in nearly $50 million in property damages,” Shreedharan says. “It was a wake-up call. We want to understand how and why it happened at such a shallow depth, if the Wasatch Fault dips so steeply at the surface.”

The Probability of the Next Big Quake

According to the Working Group on Utah Earthquake Probabilities, there is a 57% chance of a magnitude 6.0 or greater earthquake and a 43% chance of a magnitude 6.75 or greater event along the Wasatch Front in the next 50 years. The central segments, which last ruptured over 1,400 years ago, are particularly concerning, as they exceed their average 300-year recurrence interval by centuries.

Having one of these quakes happen can cripple water systems, roads, and unreinforced buildings. This can cause upward of $629 million in damages and take quite a toll on the economy.

The Weakness Beneath the Surface

Recent studies reveal that the Wasatch Fault’s hidden fragility lies in rocks shaped by forces older than the mountains. Analyses of fault zone samples show the rocks are unusually weak and slick, and this ancient weakening, combined with repeated seismic activity, has primed the fault to slip more easily than previously assumed.

“You can envision how slick rock can slide more easily and at lower angles than a rock with a rough surface,” he says. “This process is happening continuously, though at a very slow pace, under our feet.”

What a Major Quake Could Do

If a major quake were to finally break free, the aftermath would be devastating. A magnitude 7.0 event, especially on the Salt Lake City segment, could cause intense ground shaking with little warning as the fault dips beneath the city itself. This would most likely bring on landslides, liquefaction, and flooding, causing surface ruptures that would displace the ground by up to 20 feet.

Economic losses are projected to reach $40 billion or more, with thousands of potential fatalities and tens of thousands injured or displaced. Although the 2020 event was much smaller than what might come, it shows how vulnerable the region is to a larger event.

Preparedness and Public Awareness

The media is constantly flooded with potential warnings of the threats around us, and taking every single threat seriously can be hard. Sometimes, it’s better to be prepared, no matter the situation’s outcome. The fact is, many Utahns remain underprepared for a major event to take place. “I feel anxious and scared. I feel like I’m terrified to have another earthquake because I feel like it will be worse, so I am sure the 2020 quake affected the fault line somehow,” said Kymmy Pitkin, a first-year student at SLCC. “I don’t feel like we as a state are prepared if we have another one.”

Efforts like the Great Utah ShakeOut drill and programs like “Fix the Bricks” aim to increase readiness and retrofit vulnerable buildings. “Awareness-wise, I’m probably more prepared that way,” said Anna Straup, a substance abuse counselor student at Salt Lake Community College. “Do I want to be more prepared? Yes. I have food storage, and I try to rotate it out, but I don’t think it is sufficient for that magnitude of event. But what I have is enough for immediate needs, not long term.”

Explore more of our trending stories and hit Follow to keep them coming to your feed!

Don’t miss out on more stories like this! Hit the Follow button at the top of this article to stay updated with the latest news. Share your thoughts in the comments—we’d love to hear from you!