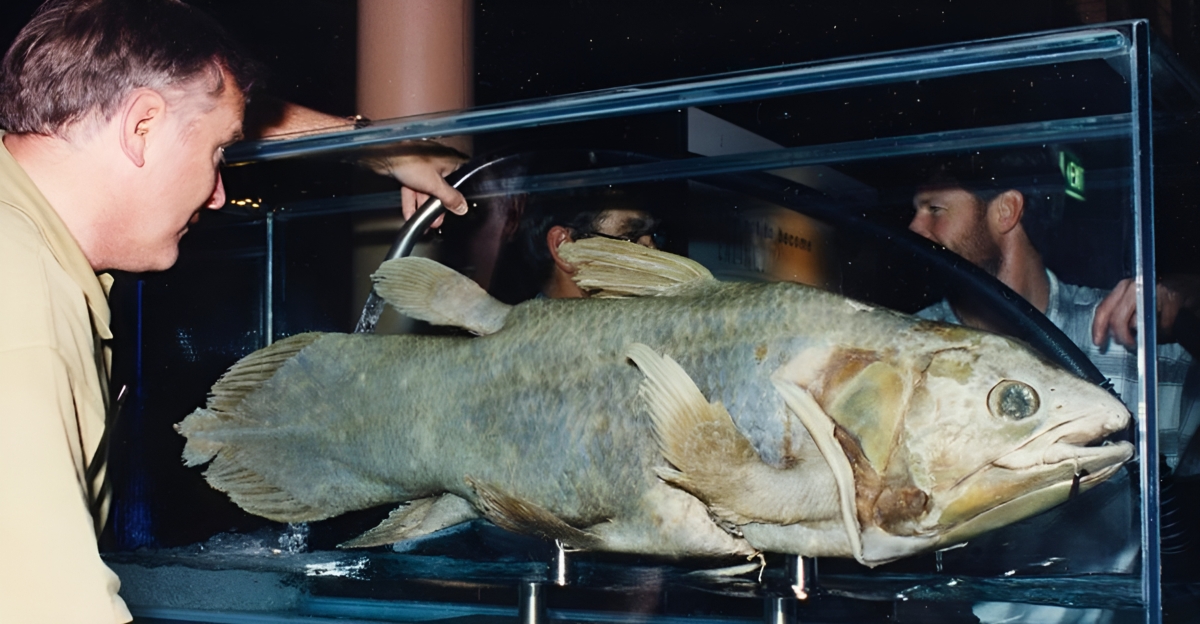

It’s one thing to rediscover a species that hasn’t been seen for a few years but to stumble upon a species that has been missing for more than 70 million years is worth mentioning. This “living fossil” was photographed nearly 475 feet below the ocean’s surface for the first time ever.

The First Photographs in 70 Million Years

This ancient fish was caught on camera for more than 70 million years in Indonesian waters by marine biologist Alexis Chappuis and support team, UNSEEN Expeditions. While the coelacanth was famously rediscovered in 1938 and later photographed in shallow Indonesian waters in 1998, these new images capture it actively navigating its twilight-zone ecosystem.

“The coelacanth, often mistakenly called a ‘living fossil’ or ‘dinosaur fish,’ had been known from fossils dated back to more than 400 million years – way before dinosaurs – and was thought to be extinct until 1938, when a specimen was discovered in a fishing net off the coast of South Africa. This marked one of the biggest natural history discoveries of the 20th century,” Watchmaker Blancpain’s release read.

The Challenge of Deep-Sea Exploration

Deep-sea diving has some serious dangers and challenges, but these researchers decided to take on the risk for the greater good. Reaching depths beyond 450 feet requires overcoming crushing pressures exceeding 150 atmospheres, near-freezing temperatures, and complete darkness. These extreme conditions needed specialized equipment like mixed-gas rebreathers, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and advanced imaging systems, with exploration costs often exceeding $50,000 daily.

After only being in the water for a few minutes, divers had to decompress for hours, floating only a few feet below the surface in the open ocean.

The Mysterious Living Fossil

Seeing the anatomy of this remarkable fish is like taking a glimpse into the past. Unlike most modern bony fish, coelacanths are lobe-finned, sharing a closer relationship with lungfish and, by extension, the ancestors of all land vertebrates. They have a hinged skull, a primitive notochord, and an electrosensory organ in the snout.

Their distinctive limb-like fins, robust internal skeleton, and unique cranial structures have remained unchanged since the Devonian period, which is why they are called the “living fossil.” As marine scientist Jessica Gordon explains, “It’s not just a fish… it’s a masterpiece in the history of evolution.”

The 1938 Sensation

On December 22nd, 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, the East London Museum curator in South Africa, spotted a bizarre, blue-scaled fish with fleshy, limb-like fins among a fisherman’s catch from the Chalumna River. She quickly realized the fish’s relevance. She contacted ichthyologist J.L.B. Smith, who, upon examining her drawings and later the specimen itself, immediately recognized it as a member of a group thought extinct since the dinosaurs.

Smith’s famous telegram—”Most Important Preserve Skeleton and Gills = Fish Described,” shows just how important this discovery was. The fish was later declared a “Lazarus taxon,” a label for species seemingly vanishing from the fossil record only to reemerge unexpectedly.

An Ancient Survivor’s Unique Lifestyle

These elusive fish retreat to underwater caves and crevices, often at depths between 328 and 1,640 feet, where the cool, stable temperatures help them conserve energy and avoid predators. These fish come out at night, drifting along ocean currents and hunting with their limb-like fins, which are surprisingly agile.

They mainly prey on benthic fish, squid, and cephalopods using their specialized rostral organ, which senses electrical fields. Their slow metabolism, low reproductive rate, and highly specialized habitat make them vulnerable to environmental changes.

Reproduction and Vulnerability

These fish have a very unusual way of reproducing, which isn’t common under fish. These fish make use of internal fertilization, which is followed by an extremely long gestation period. They are believed to carry this live young anywhere from 13 months to three years. Embryos develop inside the mother, nourished by a large yolk sac, and are born as miniature versions of adults, typically numbering from five up to twenty-six pups per litter.

Females may only reproduce every two or more years and do not reach maturity until they are at least 16 to 20 years old. Genetic studies indicate that coelacanths tend to have a monogamous mating system, with each clutch sired by a single male, and there is no evidence of parental care after birth.

The Coelacanth’s Place in Evolutionary History

Researchers rarely get the opportunity to study something other than a fossil when it comes to understanding evolution. These fish are both a relic of ancient marine ecosystems and a critical reference point for understanding vertebrate adaptation to land.

While genomic analyses confirm lungfish, not coelacanths, as the closest living relatives of tetrapods, these lobe-finned fish retain anatomical and genetic blueprints that predate the Devonian water-to-land transition by over 400 million years.

Two Living Species

Today, only two living species of coelacanth are known to science: the West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and the Indonesian coelacanth (Latimeria menadoensis). The West Indian Ocean coelacanth can be found in deep, rocky slopes and caves off the coasts of the Comoros Islands, Madagascar, Mozambique, Kenya, and even South Africa.

The Indonesian coelacanth can be found in Indonesian waters, particularly near Sulawesi and the Maluku Archipelago. Although these fish have very subtle differences, they are both critically endangered, with small, isolated populations left.

Protecting These Living Fossils

Although these fish have managed to survive for millions of years, the modern threats they face are rapidly increasing, and they aren’t able to adapt fast enough. Both species are listed on the IUCN Red List due to their extremely limited populations and highly specialized deep-reef habitats.

Their slow growth, late maturity, and infrequent reproduction make recovery from population losses exceptionally difficult. “This discovery highlights the rich biodiversity of North Maluku and underscores the urgency of further exploration and conservation of the mesophotic zone,” Dr. Gino Valentino Limmon, a researcher at Pattimura University and expedition partner, said in a statement.

Explore more of our trending stories and hit Follow to keep them coming to your feed!

Don’t miss out on more stories like this! Hit the Follow button at the top of this article to stay updated with the latest news. Share your thoughts in the comments—we’d love to hear from you!