A small, unassuming dog pelt from 1859, rediscovered in a Smithsonian archive, has illuminated a lost chapter of Indigenous history. The Coast Salish woolly dog, extinct for over a century, was a vital part of the cultural and economic fabric of Pacific Northwest communities. Now, genetic analysis of the pelt—called “Mutton”—has offered new clues to the dog’s ancestry, its role in Salish traditions, and the devastating impacts of colonization that led to its disappearance.

5,000 Years in the Making

The Coast Salish woolly dog did not evolve by accident. DNA analysis shows that his breed diverged from other dogs about 5,000 years ago, making it one of the earliest examples of selective breeding in the Americas. Indigenous communities carefully bred these dogs for their wool, shaping a lineage that was distinct in its genetic traits. This intentional breeding emphasizes the role of woolly dogs as a resource for creating ceremonial textiles and maintaining cultural traditions across generations.

A Source of Warmth and Wealth

The woolly dog’s thick coat wasn’t just practical but also essential. Coast Salish communities used its wool to craft blankets and robes, symbols of wealth and status that also held spiritual significance. Women of high rank sheared the dogs’ fleece like sheep, spinning it into yarn that was often combined with mountain goat hair. The resulting textiles were valued for their warmth, beauty, and cultural importance, serving as more than just clothing—they were artifacts of identity and tradition.

Diets Designed for Quality Wool

To produce fleece suitable for weaving, woolly dogs required special care. Chemical analyses of Mutton’s pelt suggest the dogs were fed a protein-rich diet, likely including fish, to maintain the quality of their wool. This level of attention reveals the depth of knowledge Coast Salish people had about animal husbandry. By ensuring their dogs’ health and optimizing their coats, Indigenous caretakers ensured the success of their weaving traditions and sustained the cultural practices tied to them.

Special Cultural Significance

Beyond being animals, woolly dogs were also integral to Salish social structures and ceremonies. They were kept separate from other breeds to maintain their distinctiveness, a practice that reflects their unique value. Blankets woven from their fleece were used in ceremonies, as gifts, and as trade items. The dogs’ role was inseparable from the identity of the Coast Salish people, making their eventual extinction a profound cultural loss.

European Contact: A Turning Point

The arrival of European settlers in the 18th century disrupted life for Indigenous peoples, and the woolly dog was no exception. Colonists introduced new breeds, which interbred with local populations, diluting the woolly dog’s carefully maintained traits. At the same time, disease and forced displacement devastated Indigenous communities. These disruptions weakened the social and economic structures that supported the woolly dog’s survival, setting the stage for its extinction.

Colonial Policies and Bans on Tradition

Colonial governments also went beyond physical displacement to target cultural practices. Policies that criminalized traditional weaving and animal husbandry further endangered the woolly dog. Women, who played a central role in caring for the dogs and weaving their wool, faced imprisonment and fines for trying to preserve these traditions. The loss of the woolly dog was not just a biological extinction but also a cultural one, as colonial authorities sought to erase all practices tried to Indigenous identity.

A Sudden and Tragic End

By the late 19th century, the Coast Salish woolly dog was extinct. Epidemics like smallpox had decimated Indigenous populations, leaving few caretakers for the dogs. The introduction of machine-made textiles further diminished the need for their fleece. Despite efforts to preserve the breed, colonization’s pressures were too great. The extinction of the woolly dog marked the loss of a unique species and the collapse of a cultural system that had sustained it for millennia.

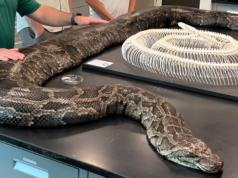

A Pelt Brings the Past to Life

Mutton’s pelt, preserved since 1859, offers a rare glimpse into this lost breed. DNA analysis revealed that Mutton’s genetics were surprisingly pure, showing little interbreeding with European dogs. This purity suggests that Indigenous communities worked diligently to preserve the breed’s unique traits, even during periods of upheaval. The study of this pelt has provided crucial insights into how the woolly dog was bred and cared for, shedding light on a vital piece of Salish heritage.

Reconstruction: A Visual Tribute

Using Mutton’s pelt and archaeological evidence, researchers have recreated the woolly dog’s appearance. Small, with a dense, fluffy coat, it resembled Arctic spitz breeds—though it was genetically distinct. This reconstruction helps modern audiences visualize the woolly dog and its unique traits, bridging the gap between historical accounts and physical evidence. Such work not only honors the breed but also sparks greater interest in the history of Indigenous animal stewardship.

Science Meets Oral Tradition

The rediscovery of the woolly dog’s story would not have been possible without the input of modern Coast Salish communities. Oral histories provided invaluable context, explaining how the dogs were bred, cared for, and integrated into cultural practices. This collaboration demonstrates the power of blending traditional knowledge with scientific methods, creating a fuller picture of the woolly dog’s place in history and its significance to Indigenous peoples.

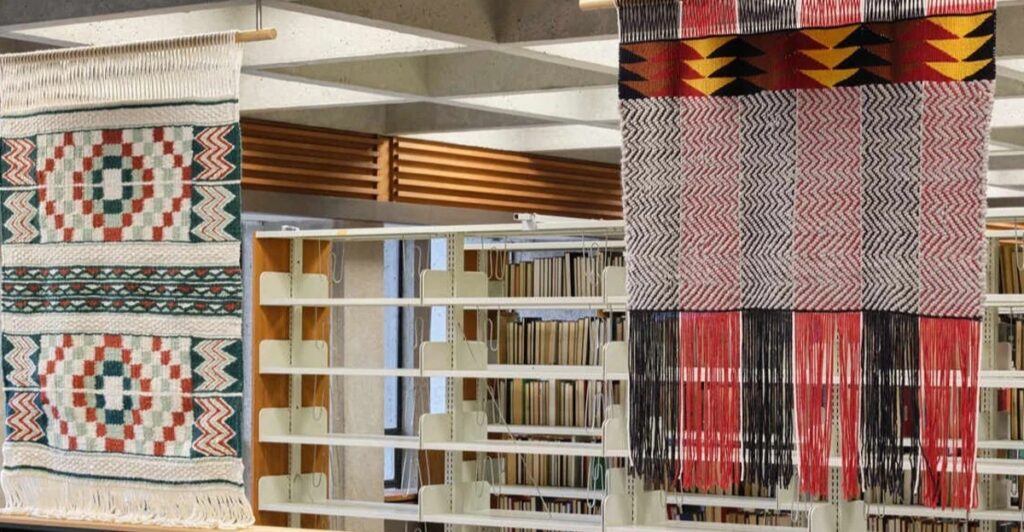

Weaving Traditions Persist

Although the woolly dog is gone, Coast Salish weaving continues to thrive. Today’s weavers draw inspiration from ancestral techniques, preserving the patterns and methods passed down through generations. By keeping these traditions alive, they honor the memory of the woolly dog and the cultural systems that once revolved around it. The practice of weaving remains a living link to the past, ensuring that this history is not forgotten.

Reclaimed Through Memory

The story of the Coast Salish woolly dog is one of connection, loss, and rediscovery. Through scientific study and Indigenous collaboration, this extinct breed’s role in history has been revived, offering a deeper understanding of the Coast Salish people’s relationship with the natural world. Though the woolly dog is gone, its legacy lives on in the cultural practices it helped sustain—exemplifying the enduring power of memory and tradition.

Resources:

- Hakai Magazine: The Story of the Indigenous Wool Dog Told Through Oral Histories and DNA

- Smithsonian Institution: Mutton, an Indigenous woolly dog, died in 1859−new analysis confirms precolonial lineage of this extinct breed, once kept for their wool

Stay connected with us for more stories like this! Follow us to get the latest updates or hit the Follow button at the top of this article, and let us know what you think by leaving your feedback below. We’d love to hear from you!