In Australia, there has been a long, expensive, and so far largely futile war against the cane toad. These troublesome, hopping marauders, originally brought in to control pests, have instead become one of the country’s most unwanted invasive species, killing native animals.

They’ve outwitted every attempt to control them. Scientists, however, are now turning the tables, using the toads against the toads themselves. A new monster has emerged from the lab: a genetically altered cane toad that will never grow up.

It swims. It eats. It remains young forever. And it craves toads of the same species. An ageless tadpole, bred by a single gene mutation, that could be nature’s most ironic assassin. But is this really the right solution? Or is it a new problem waiting to happen?

Say hello to the Peter Pan Toad

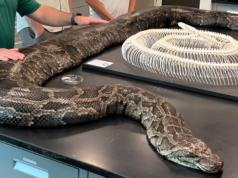

Dubbed the “Peter Pan” toad, this genetically modified creature will never mature. Researchers at Macquarie University found that by removing a single gene that controls the production of the hormone thyroxine, the trigger for metamorphosis, cane toads may be prevented from metamorphosing.

These tadpoles are longer-lived, grow bigger, and acquire a voracious appetite. Unlike regular tadpoles, they don’t undergo metamorphosis into land-hopping adults. Rather than marching out, they remain in the water, feasting on… other cane toads. Unusual as it sounds, this biological peculiarity would make them a perfect population-control agent, if used wisely.

How Gene Editing Freezes Metamorphosis

The biology is surprisingly elegant. Cane toads, like most amphibians, use a hormone called thyroxine to induce their metamorphosis from tadpole to adult toad. By “knocking out” the gene that creates this hormone, researchers basically stop the process in its tracks.

The outcome? A form of living limbo; a toad that eats like a champion but never grows legs or lungs. This method doesn’t introduce anything synthetic or foreign into the gene pool. It merely deletes a naturally occurring gene.

That subtlety is one of the reasons scientists think the dangers of this organism getting out of control are less risky than other forms of genetic modification.

Cannibals by Nature, Super-Cannibals by Design

Cane toad tadpoles already possess a dark secret: they are cannibals. In Australia, the cannibalization of their own kind is more than twice that in their native continent of South America.

Peter Pan tadpoles are even more extreme than regular tadpoles. In experiments, they consumed three times as many eggs as regular tadpoles. The experiments had a zero survival rate of eggs in ponds when older gene-edited tadpoles were present.

Still more interesting, it appears that they prefer their own type of eggs and ignore frog eggs, indicating a clear pattern of predation. These behaviors make them an incredibly strong contender for controlling invasive toad populations from within.

Why Cane Toads Are Such an Issue

They were brought in 1935 as a form of biological control to feed on sugarcane beetles, but cane toads soon became pests. Having few natural predators and reproducing at an incredible rate, up to 30,000 eggs per brood, twice a year, their numbers exploded.

Today, there are an estimated 200 million toads in north Australia alone. They’ve poisoned native wildlife that attempts to consume them, fought others for food, and dispersed to virtually every northern state.

Conventional control measures such as “toad busting” have made little impact. That’s why researchers are testing early-stage controls such as the Peter Pan toad in the hopes of halting the cycle before toads become problematic.

Why Not Just Release Them Everywhere?

But here’s something even more surprising about Peter Pan toads. Since they never mature, they are unable to reproduce. This limits their ability to expand. At present, every gene-edited tadpole has to be made artificially – a time-consuming and costly process of injections into individual eggs.

One possible solution being tested is supplementing the water with synthetic thyroxine to temporarily bypass the gene block and enable some of the tadpoles to develop into adults – long enough, at least, to give birth to a batch of cannibalistic offspring. If perfected, this could provide self-renewing waves of gene-altered tadpoles, bred in captivity and released into specific hotspots.

But Is It Safe for the Ecosystem?

Things get complicated now. The dangers aren’t hereditary: these tadpoles can’t breed or transfer mutations. There are still ecological risks, however. What happens when you introduce big, meat-eating, long-lived tadpoles into ecosystems that are home to birds, fish, and turtles, too, which live in water?

Could the Peter Pan toads outcompete or kill other creatures? The experiments up until now have taken place in laboratories. Future field trials in Western Australia will seek to answer those questions first. The researchers are particularly keen to focus on areas where toads breed only in artificial wetlands and thus rule out the possibility of ecological dispersal.

Learning from the Past — The Cane Toad’s Original Sin

Necessarily, however, cane toads themselves are a case study of a biological “solution” that spectacularly failed. Brought in from Hawaii to control beetles in Queensland’s cane fields, they didn’t eat the beetles and soon enough bred out of control.

That decision still haunts Australian environmental history. Unsurprisingly, any suggestion of releasing genetically modified toads is being met with resistance. Scientists today are anxious not to repeat the same mistakes.

Unlike the 1935 indiscriminate import, the move this time is being well examined ethically and ecologically. That includes risk tests, government regulation, and substantial testing prior to more general usage.

What the Experts Say

Study leader Professor Rick Shine insists it’s not a “gene drive”: no new DNA is being added and breeding is stunted. Curtin University Professor Ben Phillips, unconnected to the study, finds the concept interesting and potentially good for managing breeding in remote or outlying areas.

He recognizes the genetic risks as low but calls for further study of possible ecological effects. Both scientists concur: the idea is promising but needs to be handled with caution. If it works, it might provide an ecologically harmless, species-specific weapon in a field where good solutions are rare.

The Future of Toad Control?

Might the Peter Pan toad rewrite the pest control rulebook? If everything goes safely in future trials, this bizarre little cannibal could turn out to be the unexpected hero of Australia’s biosecurity campaign.

It’s an odd exception to the rule of combating fire with fire. Instead, we’re fighting cane toad with cane toad. The scheme won’t necessarily kill off the toads forever, but it should decimate their populations significantly and buy indigenous animals some time to recover.

As with any environmental treatment, the next steps must be carefully considered. But all in all, it’s clear that the Peter Pan toad has presented us with a new tool in the battle against invasive species.

Explore more of our trending stories and hit Follow to keep them coming to your feed!

Don’t miss out on more stories like this! Hit the Follow button at the top of this article to stay updated with the latest news. Share your thoughts in the comments—we’d love to hear from you!