Paleontologists recently discovered fossilized footprints from 280 million years ago (way before dinosaurs existed), in Grand Canyon National Park. These tracks were made by four-legged beasts, early tetrapods, that the desert, ages before it became the Grand Canyon. The strange thing is, their footprints look like tread marks…

A Rocky Discovery

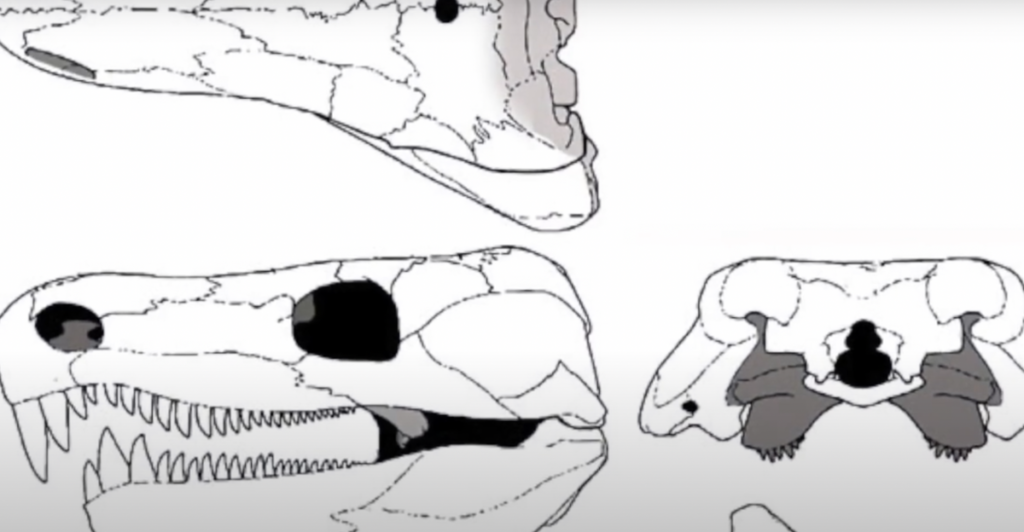

The tracks are on a big sandstone boulder, deep in the canyon. Scientists found them in 2017 and realized there was something different about them. These marks came from an ancient group called early vertebrates called diadectomorphs, beings that blurred the line between amphibians and reptiles.

Meet the Trackmakers

Diadectomorphs didn’t look like any desert creature we know. They were stocky, with short legs and five toes. They had no claws and walked on all fours. Scientists assumed that, like most animals, they needed water to survive, but these marks question that idea.

Why This Is a Big Deal

Prior to this discovery, scientists thought only reptiles could survive in dry landscapes. But these tracks, found in the Coconino Sandstone, are proof of something else. They’re evidence of diadectomorphs prospering in a desert-like, dry environment, making scientists re-think what we knew about evolution.

What Is Ichniotherium?

The footprints belong to a type of track called Ichniotherium (ICK-nee-oh-THAY-ree-um). Prior to this, scientists had only seen these prints in Europe, in damper climates. Finding them in a desert setting was utterly unexpected.

The Oldest of Its Kind

This is not just the first ever Ichniotherium track in a desert. It’s also the youngest one. This means these creatures lived longer than scientists believed, potentially adapting in ways we don’t know.

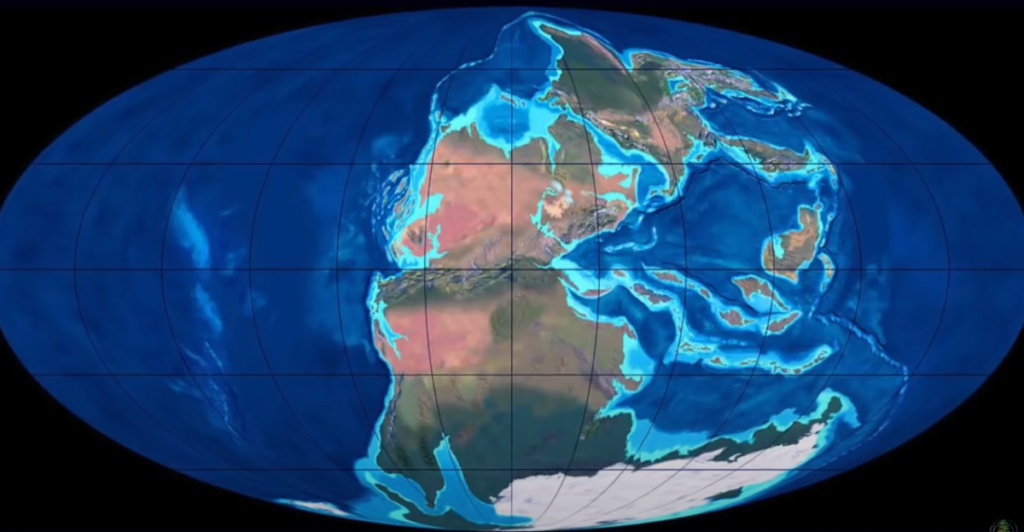

Desert Life Before Dinosaurs

Two hundred eighty million years ago, this part of the globe wasn’t a canyon. It was a sandy desert, with rolling dunes. Wind-blown landscapes, scorching heat, and, it seems, diadectomorphs wandering around the dry world.

How Fossils Get Preserved

The prints lasted so long because they were pressed into soft sand that, over time, hardened into stone. The shifting topography over millions of years covered them up and preserved them, waiting for the optimal time (and the right scientists) to expose them.

A Surprising Adaptation

Diadectomorphs were not reptiles, so how did they manage to make it in such dehydrated conditions? Scientists don’t know for sure, but it implies these animals possibly had survival tactics like burrowing under the ground or growing thicker skin to conserve water.

The Fossil History of the Grand Canyon

This is not the first fossil discovery at the Grand Canyon. The park has a history of paleo finds, but these particular tracks are noteworthy because they rewrite what we thought about what creatures are able to survive in a desert.

The Science Continues

Brazilian, German, and American scientists are still studying these prints. They’re measuring, mapping, and analyzing them to see what exactly they tell us about early tetrapod evolution.

What This Means for Evolution

This finding proves that evolution is not always black and white. Diadectomorphs were not built for the desert, yet they clearly were there, leaving tracks on ancient sand dunes. It’s evidence that nature and evolution will find a way.

A Walk Through Time

The Grand Canyon has a history as old as millions of years, and these impressions are one of its mysteries. The tracks discredit what we thought we knew about primitive life and prove that science remains dynamic.

Discover more of our trending stories and follow us to keep them appearing in your feed

California Is Breaking Apart: A Fault Line Is Forming Faster Than Anyone Predicted

“There Will Be Eruptions”: Concerns Mount as Yellowstone Supervolcano Activity Shifts

Philanthropist Promises To Cover $771.23M Annually After US Exit From Climate Accords

The War on Cows Is Over—And Green Extremists Have Lost

References:

Reference 1

This article first appeared here

Stay connected with us for more stories like this! Follow us to get the latest updates or hit the Follow button at the top of this article, and let us know what you think by leaving your feedback below. We’d love to hear from you!