In a dramatic wildlife comeback, the Guam kingfisher, declared extinct in the wild for roughly 40 years, is now laying eggs in the most unlikely of places: a remote American atoll called Palmyra. The vivid, reddish-brown bird, or Sihek as it is locally known, once vanished completely from its native island of Guam due to the introduction of the brown tree snake.

Decades of captive breeding and conservation success have paid off, with the species now back in the open air, nesting and laying eggs in a predator-free U.S. sanctuary. Let’s take a look at this biological triumph and this bold new chapter where extinction is being rewritten in real time.

The Bird That Vanished

The Guam kingfisher wasn’t just another casualty of extinction; it was a warning bell. Once common in Guam’s forests, the sihek population declined significantly by the 1980s due to the accidental introduction of the brown tree snake to its habitat during World War II.

The native bird populations were decimated by the snakes, which preyed on eggs, chicks, and adult birds with little resistance. By 1988, there were no more sihek inhabiting the wild.

Conservationists struggled to save 29 individuals, setting up a last-ditch captive breeding program in American zoos. It was a symbol of ecological vulnerability—and hope—for biologists racing against extinction all over the world.

A Pacific Sanctuary

Palmyra Atoll, a distant American chain of islands south of Hawaii, became an unlikely refuge for the sihek. Managed under cooperation with The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, this atoll gave them two valuable conditions: isolation and protection.

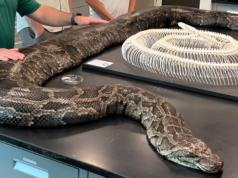

No predators, snakes, or human beings—just dense forests and a healthy insect population. Conservationists released nine sihek on the atoll in late 2023, where they hoped that the birds might survive and eventually breed.

The site was a biological dress rehearsal for their eventual return to Guam. But then something surprising happened: not only did the sihek thrive, they started laying eggs again.

The Eggs That Changed Everything

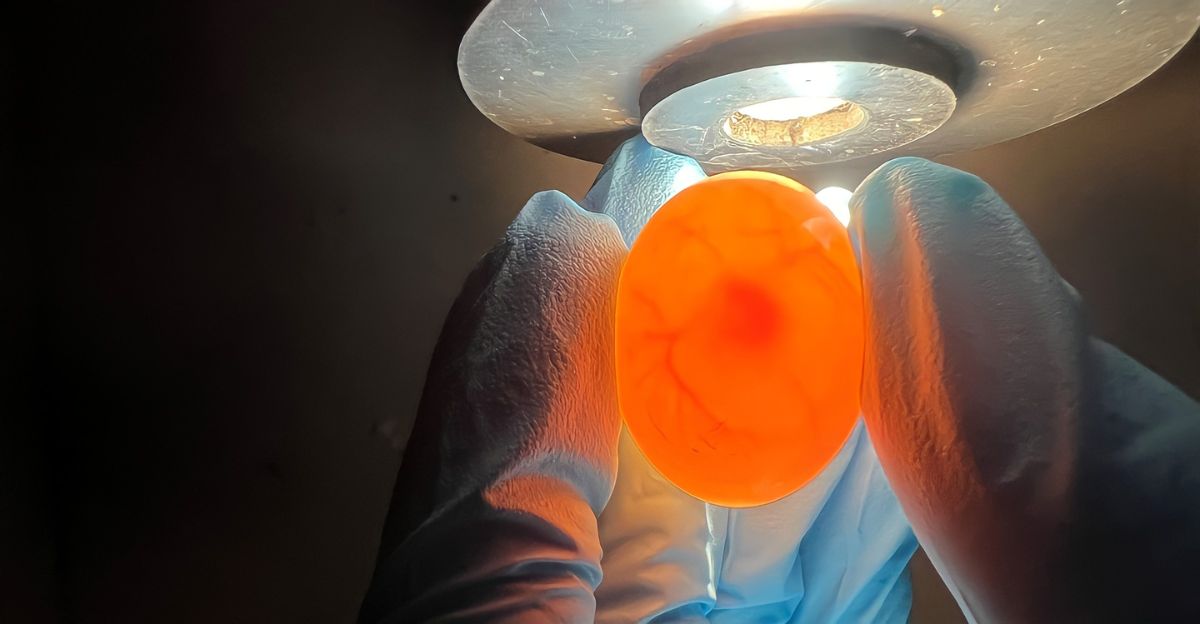

On March 31, 2025, scientists found the first sihek eggs laid in the wild in nearly 40 years. It wasn’t just a nest—it was proof that concerted conservation efforts were successful.

Of the four breeding pairs released on Palmyra, three successfully established bonds and started nesting. The eggs marked the beginning of a new wild population, demonstrating that the species could survive—and thrive—outside of captivity.

Scientists monitored the nests with discreet camera traps and telemetry, monitoring courtship and nesting behaviors, as well as territorial vocalizations. The birds had acclimatized quicker than expected, surprising even seasoned researchers. For the sihek, extinction in the wild is officially history.

From Cultural Icon to Scientific Victory

The site is more than a conservation story—it’s a living force of CHamoru identity, Guam’s Indigenous population. For hundreds of years, the site has been part of cultural stories, songs, and imagery.

Its disappearance wasn’t just an ecological loss; it severed the spiritual link between Guam’s people and their environment. Returning the sihek to the wild, even in exile, is greater than biodiversity—it’s cultural resurrection.

Palmyra can’t be Guam, but it’s a lifeboat for the bird’s safe return. CHamoru leaders and scientists are working together so that future generations won’t learn about the sihek in museums alone—they’ll watch it fly again over their homeland.

Science, Zoos, and Unlikely Partnerships

It took nearly four decades, dozens of institutions, and unlikely partnerships to get here. The sihek breeding program spans 25 facilities across the U.S., including the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and the Sedgwick County Zoo.

Unlike typical zoo projects, this one wasn’t about exhibition but rather preservation. Each bird was recorded, tracked, and painstakingly bred and cared for to preserve genetic diversity. The final release required federal approval, ecological modeling, and international consultation.

Further, scientists had to replicate indigenous diets, provide survival skills training, and even rewild birds that had previously hatched in cages. The project aimed to revive a bird most of us had never heard of—and it worked.

High-Tech Birdwatching

The modern conservation landscape is more like Silicon Valley than Jurassic Park, where radio telemetry, GPS collars, and drone-guided habitat mapping track the sihek’s movement on Palmyra.

Birds in nests are watched with unobtrusive infrared camera traps, and artificial intelligence sorts through thousands of hours of footage to identify behavior, such as mating calls and egg incubation.

All this technology ensures real-time information without human interference. The endeavor also provides a model for other species that are already or on the verge of extinction in the wild, illustrating how biology and technology can be used to reverse what was once thought to be irreversible.

The Snake in the Garden

Though heartening as the Palmyra achievement is, getting the sihek back in Guam—the project’s ultimate goal—is still decades away. The brown tree snake is still entrenched throughout the island, despite decades of trying to eradicate it.

Guam spends millions of dollars annually to keep the snake from invading various ecosystems. Biologists are experimenting with genetic engineering, poisonous bait, and snake-sniffing canines, but a solution is nowhere in sight.

Thus, the sihek cannot be reintroduced into its native habitat until the intruding snake population is brought under control or eradicated. The bird’s story may be heartening, but it is also a cautionary tale.

Extinction Isn’t Always Forever

The sihek’s comeback forces us to reexamine our understanding of extinction. For decades, the birds thrived only in captivity—out of mind, out of sight, and technically “extinct in the wild.”

But Palmyra demonstrates that with science, patience, and investment, wild extinction does not have to be forever. It can be reversed and may not always be the death of a species but rather a mere interlude.

Conservationists now see “extinct in the wild” as a temporary setback, not an irreversible state. The sihek is not unlike the California condor and Arabian oryx, which are Lazarus species. If extinction is reversible, how many other creatures are waiting in line?

A Blueprint for the Future

The sihek’s story isn’t the story of one bird. It’s the story of how the future of conservation is advancing. It’s about science and cultural reclamation.

The stage has been set: select a refuge habitat, breed with genetic diversity, take advantage of technology, and prioritize long-term investment over short-term media attention. Conservation takes a long time and isn’t cheap, but it has proven to be effective.

As we see unprecedented species loss, Palmyra is a shining example of what can be achieved. The sihek is soaring again, and if we can bring this species back from the brink of extinction, what else can we save?

Explore more of our trending stories and hit Follow to keep them coming to your feed!

Don’t miss out on more stories like this! Hit the Follow button at the top of this article to stay updated with the latest news. Share your thoughts in the comments—we’d love to hear from you!