When people think of invasive species, they picture plants or insects, not fish that leap, crawl, or even walk into new ecosystems. Yet across America’s rivers and lakes, a quiet invasion is transforming aquatic life.

Some non-native fish have pushed out native species entirely, turning diverse waters into monocultures. Even more surprising? A few of these species were brought in with good intentions, and some now support local economies. These underwater intruders aren’t just disrupting ecosystems, they’re redefining them.

From flashy aquarium escapees to ancient parasites, these nine fish are permanently altering the future of America’s waterways, often in ways no one saw coming.

Asian Carp

Introduced in the 1970s to help clean up Southern aquaculture ponds, Asian carp (silver, bighead, grass, and black carp) quickly escaped into the Mississippi River system. Their population exploded, and their nonstop appetite for plankton has devastated native fish that rely on the same food.

Today, Asian carp dominate entire stretches of river, threatening a $7 billion fishing industry and even injuring boaters with their high jumps. Originally seen as a solution to water quality issues, these fish have instead become one of the most notorious ecological threats in U.S. waters.

Lionfish

With striking stripes and venomous spines, lionfish were once prized aquarium pets. But after being released into the wild off Florida’s coast in the 1980s, they’ve become predators with no rivals. These invaders can lay up to two million eggs a year and now stretch from New England to the Caribbean.

Without natural predators, lionfish are wiping out reef fish populations at an alarming rate. Scientists warn their unchecked spread could permanently reshape reef ecosystems across the Atlantic and Gulf.

Northern Snakehead

When northern snakeheads showed up in Maryland in 2002, their ability to breathe air and wriggle across land caused a media frenzy. Nicknamed “Frankenfish,” these predators eat everything from fish and frogs to small mammals.

Their aggressive breeding and survival skills make them hard to eliminate, and while the human threat was exaggerated, the ecological damage is real. Snakeheads often outcompete native predators, rewriting food webs wherever they gain a foothold.

Zebra Mussels

Zebra mussels are tiny, but they’re wreaking havoc on a massive scale. Since their U.S. discovery in 1988, these mollusks have caused billions of dollars in damage by clogging pipes at power plants, water treatment facilities, and other infrastructure. Fast-reproducing and able to stick to almost any hard surface, zebra mussels transform human-built systems into their breeding grounds.

Unlike native mussels, they mature quickly and release millions of larvae, spreading rapidly through waterways. In many regions, they’ve decimated native mussel populations that once naturally filtered and cleaned water, forcing costly technological fixes. Zebra mussels exemplify how invasive species can cripple both nature and industry

Round Goby

Brought to the Great Lakes in ballast water during the 1990s, the round goby is a small but aggressive invader. It outcompetes native bottom-dwelling fish and feasts on the eggs of key sportfish. In a strange twist, gobies have become prey for some native predators, helping boost species like smallmouth bass.

But there’s a catch: gobies accumulate toxins from eating invasive mussels, passing those poisons up the food chain. Their rise shows how one invader can both help and harm an ecosystem.

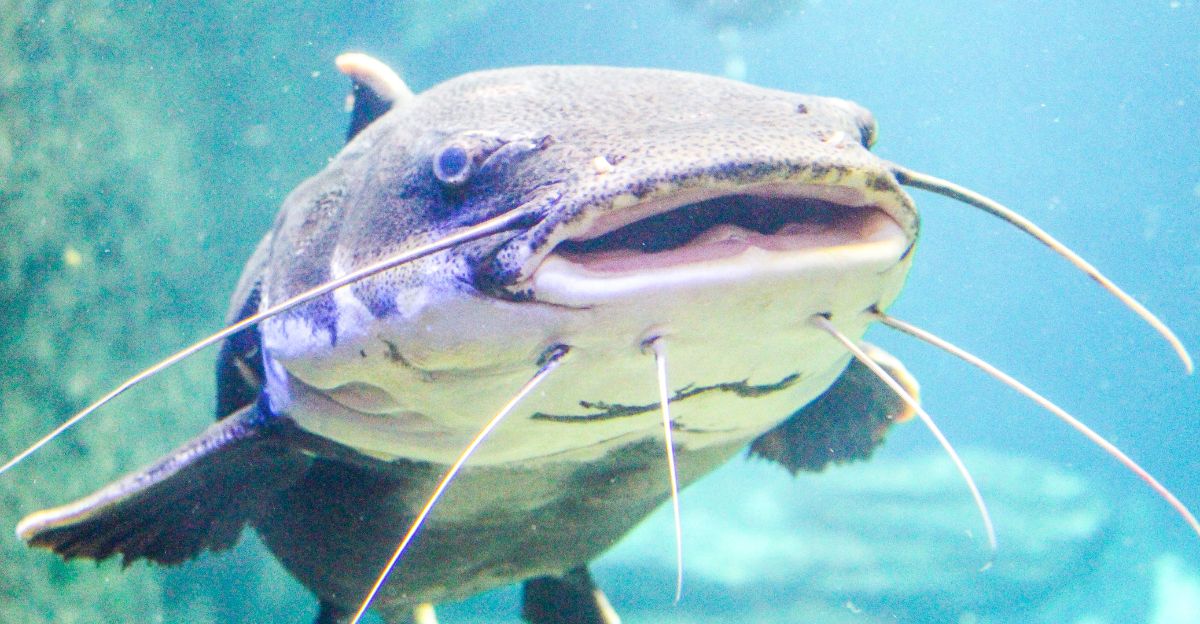

Blue Catfish

Native to the Mississippi basin, blue catfish were introduced to the Chesapeake Bay in the 1970s for sport fishing. But outside their natural range, they’ve become top predators, growing over 100 pounds and consuming everything from blue crabs to menhaden.

Their booming population is disrupting food webs and threatening valuable fisheries, including striped bass. The blue catfish story is a warning: even native species can become destructive when moved into new environments.

Common Carp

Brought to America in the 1800s as a food fish, common carp, also known as the Eurasian carp, are now one of the most widespread species on the continent. Their bottom-feeding behavior stirs up sediment, increases water cloudiness, and wrecks native spawning grounds.

Despite their destructive habits, carp are still prized in some areas for fishing and food, creating tension between economic benefits and ecological costs. Their story is a long-running example of how good intentions can leave murky legacies.

Sea Lamprey

Sea lampreys, jawless fish that latch onto victims and drain their blood, invaded the Great Lakes via shipping canals in the early 20th century. Their assault on native fish caused commercial fishing losses in the hundreds of millions.

While control efforts have reduced their numbers, they remain a costly and ongoing threat. These ancient parasites prove that even the oldest creatures can deliver devastating new consequences in modern ecosystems.

Largemouth Bass

Largemouth bass are America’s favorite sport fish, but their reputation doesn’t travel well. In regions outside their native range, especially in the West and abroad, they prey on smaller fish and amphibians, sometimes wiping out entire species.

Their status as both hero and villain challenges the idea that invasive species must come from abroad. Sometimes, the problem lies with native favorites relocated to places they were never meant to be.

The War Isn’t Just About Fish, It’s About Us

Eradicating invasive fish is rarely simple. In many areas, local economies and traditions now rely on these species for food, sport, or industry. That makes full removal both politically and practically difficult. Instead, communities are trying creative solutions, like turning carp into pet food or promoting lionfish dishes.

The fight against invasive fish isn’t just biological, it’s economic, cultural, and psychological. Winning it may mean learning to adapt, not just eliminate.

Explore more of our trending stories and hit Follow to keep them coming to your feed!

Don’t miss out on more stories like this! Hit the Follow button at the top of this article to stay updated with the latest news. Share your thoughts in the comments—we’d love to hear from you!