Extinction is not just the demise of a species—it’s the conclusion of an entire evolutionary tale. These aren’t stories of animals that went extinct billions of years before humans walked the Earth; they’re narratives of animals that evolved and died out before our eyes.

Often called “endlings,” these animals, the last of their kind, survived an unprecedented loneliness that echoes human abandonment. Their tales are potent warnings, moral dilemmas, and emotional reckonings.

As the sixth mass extinction gains momentum with human activity at its center, these nine accounts of the last members of an animal species demonstrate the price of indifference and the importance of confronting our environmental legacy.

1. Martha, the Passenger Pigeon

Passenger pigeons were once the most numerous bird species in North America—perhaps the planet. Billions darkened the skies in flocks that spread for miles as they migrated.

However, commercial logging and hunting reduced their numbers in the late 1800s, leaving Martha alone in captivity as the final passenger pigeon. She passed away at the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914.

Her death not only marked the extinction of her species but also the industrial-scale eradication of a bird that had been believed to be limitless. Martha’s solitary death forced conservationists to redefine extinction as a stark and brutal fact rather than as an abstract notion.

2. Benjamin, the Thylacine

The thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, was a carnivorous marsupial from Tasmania. It resembled a striped dog; the species was seen as a livestock killer and hunted relentlessly.

Despite actual proof, this belief continued, and it led to government bounties and widespread slaughter. Benjamin, the last thylacine known to exist, died at Hobart Zoo in 1936 when he was locked out of his shelter one cold night.

He passed away only two months after the species had been officially protected, something that came far too late. Benjamin’s final days were a bitter reminder of bureaucratic delay, misplaced paranoia, and the dangers of letting anecdotal narratives override evidence in wildlife policy.

3. Lonesome George, the Pinta Island Tortoise

Lonesome George, the last of his giant tortoise subspecies, was discovered on Pinta Island in the Galápagos in 1971. Researchers searched desperately for a mate—a genetic replacement to continue his lineage—but none existed.

As a conservation icon, George was the epitome of both hope and despair. His species had been decimated by whalers and invasive species, such as goats. George died in 2012, ending a 10-million-year evolutionary run.

His death mirrored the irony of modern conservation: global attention came, but only after irreversible loss. While George’s body was preserved, his genes and legacy are forever lost.

4. Celia, the Pyrenean Ibex

Celia was the last known Pyrenean ibex, a wild goat subspecies in the Pyrenees Mountains. She died in 2000 after being struck by a fallen tree, officially putting an end to her species.

But in a scientific twist, Celia’s DNA was preserved and used in a 2003 cloning experiment—the first successful de-extinction. However, the cloned ibex survived only seven minutes due to lung deformities. That brief life was miraculous yet cautionary.

De-extinction may recover DNA, but it can’t revive the ecosystems, habits, or cultural information that vanish when a species is lost. Celia’s story is a tale about scientific ethics as much as genetics.

5. Booming Ben, the Heath Hen

The heath hen, a member of the greater prairie chicken clan, thrived across the northeastern United States. Hunting and habitat destruction pushed it to extinction by the 1870s—except in Martha’s Vineyard.

Conservationists created a safe haven where the flock rebounded temporarily. But disease, inbreeding, and fires plagued the sanctuary. By 1929, only Booming Ben remained. His sonorous mating calls echoed unanswered across the island, giving rise to his moniker.

He was last seen in 1932. Booming Ben’s frantic cries represent one of the most tragic losses in extinction mythology—a male who survived not to reproduce but to chronicle the gradual death of his species.

6. Toughie, the Rabbs’ Fringe-Limbed Treefrog

Discovered in Panama in 2005, Rabbs’ fringe-limbed treefrogs were unique amphibians. The male guarded tadpoles in water-filled holes in the ground, an uncommon behavior within the genus.

But their rainforest habitat was rapidly destroyed, and a chytrid fungal epidemic devastated amphibian populations across Central America. As the only one of his kind left, Toughie was relocated to the Atlanta Botanical Garden for conservation.

Despite extensive efforts, no mate was ever found, and he died in 2016, effectively ending his species’ journey on this planet. His story is a parable of our era: despite scientific awareness, mass extinctions continue to occur right before our eyes.

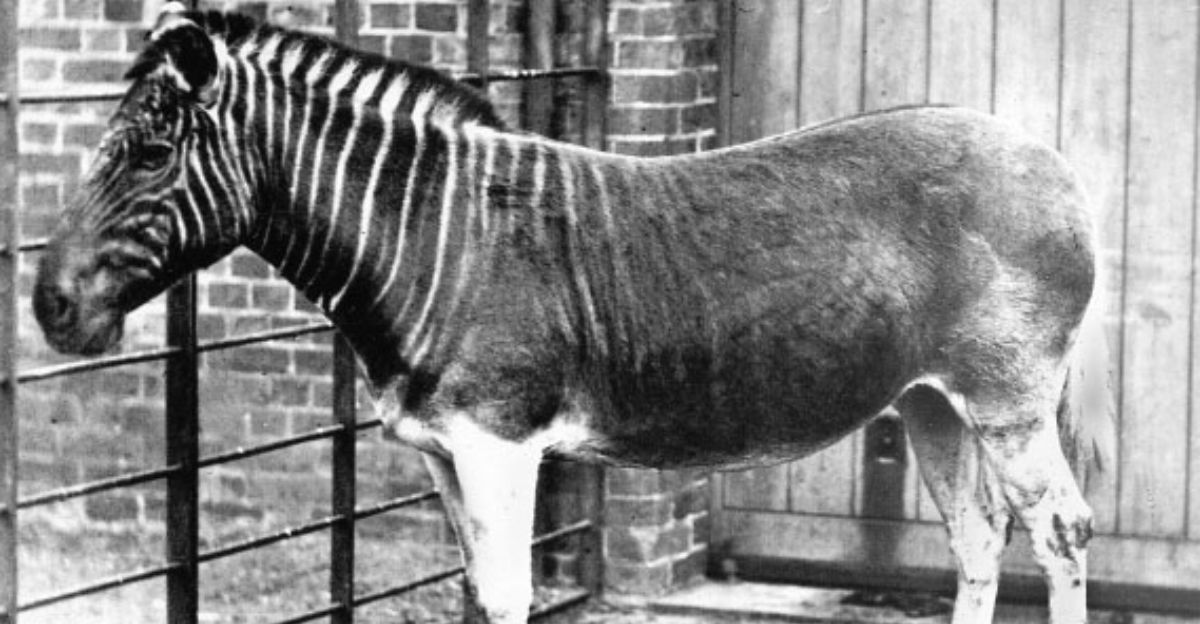

7. The Last Quagga

The quagga was a South African subspecies of zebra that possessed distinctive striping only on its head and neck, fading to brown along the rest of the body. European colonists hunted it vigorously for meat and hide. Further, Quaggas had to compete with livestock for food.

The last recorded quagga died in the Amsterdam Zoo in 1883. Unfortunately, no one realized she was the last of her kind until many years later. Moreover, it wasn’t until the 20th century that it was identified as a distinct subspecies through genetic analysis.

Its extinction went unrecorded, an eerie contrast to the viral obituaries we see today. The Quaggas’ quiet passing is a lesson in complacency towards vanishing diversity.

8. The Last Barbary Lion

Barbary lions occupied North Africa and were famous for their enormous size and dark flowing manes. Roman emperors used them in gladiator battles, and colonial hunters later exterminated what remained of the species.

The final wild Barbary lion was likely killed in Morocco in the 1940s, and the final captive lion died shortly after. Although some captive lions may have partial Barbary genetics, no purebred individuals remain.

In contrast to other animals, these lions disappeared not in a single spectacular instant but over centuries of exploitation. Their likeness can be seen in art and heraldry—especially as emblems of royalty—though the mighty beasts themselves are irretrievable.

9. The Slender-Billed Curlew

The slender-billed curlew was an uncommon shorebird migrant that bred in Siberia and wintered in North Africa and the Mediterranean. An elusive bird, its declining population went unnoticed for decades.

Losses in breeding habitat and unregulated hunting during migration routes further hastened its decline. The last confirmed recorded slender-billed curlew was in Morocco in 1995. Although there were some unsubstantiated sightings after 1995, none were positively confirmed.

No breeding pairs or nests were ever found despite intensive searches. Ornithologists regard it as one of the most tragic avian extinctions of the modern era—a disappearance so quiet, so evasive, that its loss remains uncertain, spectral, and devastatingly final.

Explore more of our trending stories and hit Follow to keep them coming to your feed!

Don’t miss out on more stories like this! Hit the Follow button at the top of this article to stay updated with the latest news. Share your thoughts in the comments—we’d love to hear from you!