Deep in southern China’s rivers, there‘s been talks about huge fish for years, one that could tip the scales at over 100 pounds. But scientists only just caught up and gave it a name. This big, bumpy-skinned creature with tiny eyes has been lurking in murky waters, mostly unnoticed by the outside world. It’s wild to think something that large stayed under the radar for so long.

Now that it’s officially declared a new species, the real story begins: how did it take so long to find, and what comes next? Let’s dig in.

Years of Clues Finally Lead Somewhere

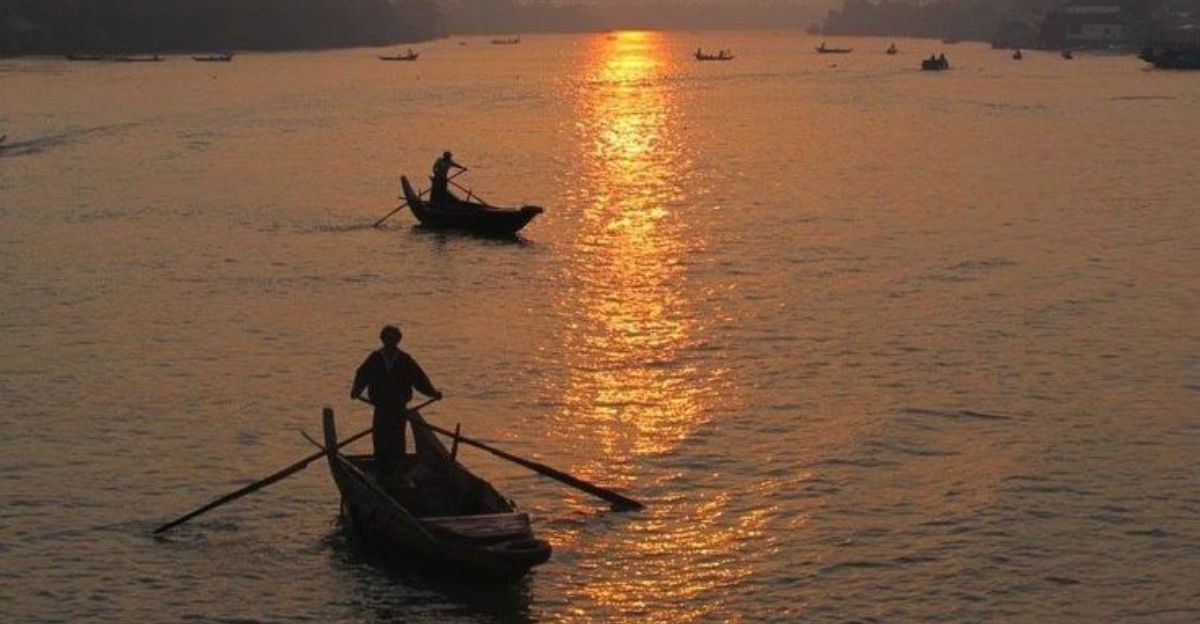

In 2004, researchers from China’s Academy of Sciences and Myanmar began surveying far-off rivers in Yunnan and the Irrawaddy basin. They noticed some huge fish that didn’t match any known species. Their fins, bones, and DNA were all different. But the findings sat in notebooks and unpublished files for years.

It wasn’t until June 24, this year, that Zeng, Chen, and others published their results. Lack of funding, difficult travel, and low priority for catfish research caused delays.

The Beast They Call Bagarius protos

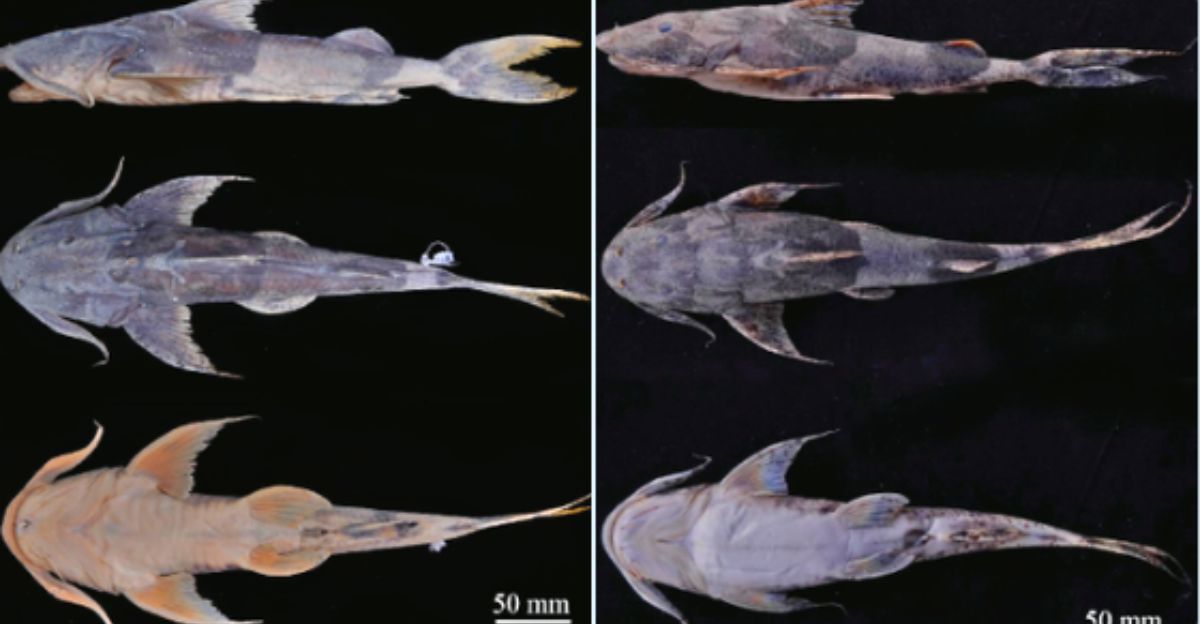

Bagarius protos lives in China’s Salween River, known locally as the Nujiang. It can grow up to 100 kg (220 lbs) and has thick skin, small eyes, and dark yellow fins. It’s missing a head ridge found in related species.

Fishers in Longling and Nanting once caught them with heavy ropes tied to rocks, using bugs and loaches as bait. Even 10-kilogram fish were common. Locals saw it as a food fish, not a mystery. Their fishing traditions show they understood the species long before scientists did. But Bagarius protos was only officially recognized this year. Another surprise was still coming.

Another Giant Emerges from Myanmar Waters

The second new species, Bagarius dolichonema, was found in Myanmar’s Irrawaddy River. It’s also been seen in India’s Manipur River and possibly in parts of northern China. It looks different from B. bagarius in a few key ways. Its dorsal spines near the adipose fin are flatter, and its vertebrae have thinner neural spines. Its pectoral fins are longer than B. protos but shorter than others.

Like protos, it eats crustaceans and fish. Its wider range suggests it can live in different types of river environments. With two new species discovered, attention turned to how they differ from each other.

How These Two Giants Are Different

Though they look alike, B. protos and B. dolichonema have key differences. B. protos has short filaments on its pectoral fins and dark yellow fins, while B. dolichonema sports longer filaments and orange or cream-colored fins. Their bones are different too ; B. dolichonema has flatter dorsal spines and thinner vertebrae between the 4th and 6th bones.

Plus, they live in different rivers: B. protos in China’s Salween and B. dolichonema in Myanmar’s Irrawaddy. These differences confirm they are two unique species important to their river systems.

DNA Finally Proved They’re New

Scientists had clues for years, but DNA testing sealed the deal. Bagarius protos showed 8.0 to 12.6 percent genetic difference from close relatives. Bagarius dolichonema had 5.7 to 12.1 percent difference. Since new species usually differ by just 2 to 3 percent, these numbers were clear proof.

DNA analysis also showed B. protos belongs to an ancient branch of the family tree, meaning it has been around a long time. Along with bones and fin shapes, the genetics gave researchers the final confirmation they needed to name both species.

Once a Food Staple, Now a Scientific Treasure

In parts of China and Myanmar, these fish were often sold fresh at markets. People cooked them regularly, never realizing they were eating species unknown to science. B. protos was caught with longlines in China, while B. dolichonema appeared in Myanmar markets.

Stomach studies showed both fed on shrimp, crab, and smaller fish, confirming their role as river predators. Many locals thought they were just bigger versions of other catfish. This everyday familiarity actually hid the fact that they were different species. While science caught up late, it proved the value of local knowledge in spotting important biological clues.

Why the Silence from Officials?

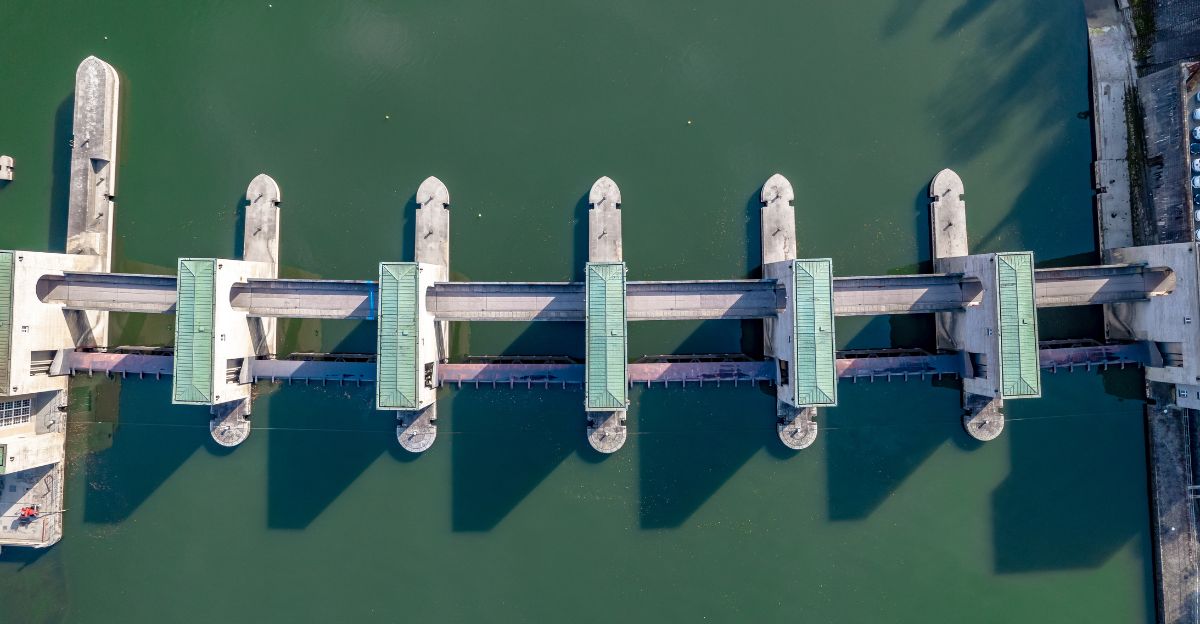

Neither China nor Myanmar has taken steps to protect these species or list them with the IUCN. That silence comes as both countries rapidly expand hydropower. China has already built 11 dams on the Lancang River and proposed 20 more on the Salween. Dams like Don Sahong and Xayaburi are underway on Irrawaddy tributaries.

Recognizing new species would require impact reviews, which might slow these projects. Robert Mather from IUCN Southeast Asia warned that protecting river life also protects food security and livelihoods. Yet so far, these discoveries haven’t changed policy. That has scientists and conservationists concerned.

Why These Discoveries Matter So Much

Rivers across Southeast Asia are packed with species the world barely knows. The Mekong alone supports over 65 million people through its fisheries, making it the largest inland fishery in the world. But 13 percent of freshwater species in the region face extinction from dams and habitat loss. These dams interrupt fish migration and disrupt the natural flood cycles that help river ecosystems thrive.

The discovery of these two giant catfish is a reminder of how much remains unknown. Without proper surveys and protections, more species may vanish before they’re even identified. Time is running out to act.

What Needs to Happen Next

Experts say several steps are urgently needed. First, both species must be added to the IUCN Red List. Governments should consider temporary protections, like no-fishing zones or gear restrictions near known habitats.

Environmental agencies must also update their assessments for upcoming dam projects to include these species. Regional cooperation through the Mekong River Commission and ASEAN is key.

Without action, these ancient river predators, only just named, could disappear forever. The science is now clear. The next move belongs to policymakers. Will these giants be saved, or will they become another warning sign ignored too late?